The real life "man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo"

and live on Freeview channel 276

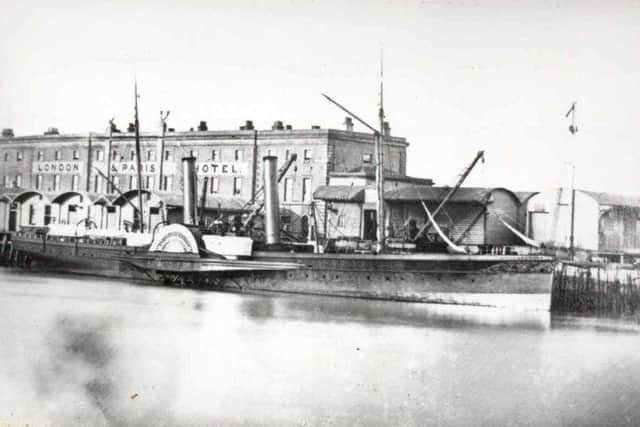

Mr Wells gained a reputation for his parties at the port town of Newhaven at the London and Paris hotel. The hotel survived for 110 years, eventually being demolished to make way for the present day roll on roll off ferry terminal.

According to Newhaven Town Council: “During the 1890s a Mr Charles Wells used to hold so many riotous parties at the hotel that he was asked to seek alternative accommodation and rented a house in Fort Road.” The popular British music hall song was published in 1891 by Fred Gilbert, later popularised by singer and comedian Charles Coborn. According to Coburn, Gilbert's inspiration was Mr Charles Wells.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the start of each day, the Monte Carlo casino funded every gaming table with a cash reserve of 100,000 francs – known as ‘the bank’. If a gambler won very large amounts, and this reserve was insufficient to pay the winnings, play at that table was suspended while extra funds were brought from the casino's vaults. This was known as ‘breaking the bank’.

The Council added: “Apparently, he actually ‘broke the bank’ at Monte Carlo three times, but despite this amazing fortune he died a pauper.”

Wells found employment as an engineer at the shipyards and docks of Marseille in the 1860s. In 1868, he invented a device for regulating the speed of ships’ propellers and sold the patent for 5,000 francs (approximately five times his annual salary).

In about 1879, he moved to Paris, where he persuaded members of the public to invest in a fraudulent scheme to build a railway. He disappeared with his clients’ money and was convicted in his absence by a Paris court.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe relocated to Britain, where from 1885 onwards he persuaded members of the public to invest in what he claimed were valuable inventions of his own devising. Although he promised substantial profits, there is no evidence that any of his backers ever received a return on their outlay. One lost almost £19,000 (equivalent to £1.9m today, allowing for inflation).